The State of America’s Birds

We must pay attention to the message that Martha left us with, and act quickly to halt declines and prevent extinctions of all America’s bird species.

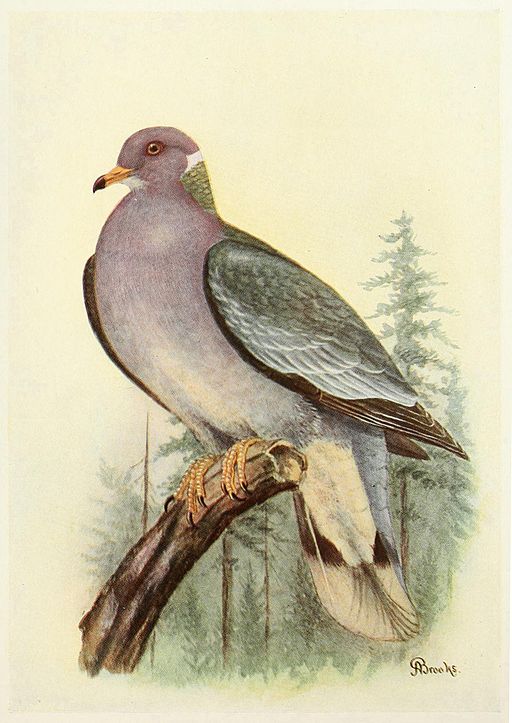

Image: By A Brooks, assumed to be Allan Brooks (Obtained from online scan at passengerpigeon00mers) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Image: By A Brooks, assumed to be Allan Brooks (Obtained from online scan at passengerpigeon00mers) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons This month saw the 100th anniversary of the extinction of the passenger pigeon. Martha, the last passenger pigeon, died in Cincinnati Zoo on the 1st of September 1914 and ever since has been a symbol of how human greed and indifference can result in the loss of a species once numbering in the billions.

The passenger pigeon was once the most abundant land bird in North America, comprising an estimated 3 to 5 billion individuals that could darken the skies for 3 days straight. The species lived only in North America, mainly east of the Rocky Mountains, and bred in the eastern deciduous forest. The passenger pigeon was so abundant because of its nomadic flocking behaviour, which meant it could exploit crops of mast and acorns that were seasonally superabundant but at unpredictable times and locations. Such large numbers was a strategy against predation, but they were unable to defend themselves against humans armed with nineteenth-century technology.

It took just 40 years for the passenger pigeon to become extinct. Humans disrupted every nesting colony, killing the birds for food and sport, and habitat loss also contributed to their downfall. This species remains a poignant example of our ability to cause the extinction of even extremely common species, and serves as a reminder to conservationists that complacency is not an option.

This month also saw the publication of the State of the Birds 2014 report, launched at a ceremony on the steps of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. The report was written by the US Committee of the North American Bird Conservation Initiative – a 23-member group of the USA’s top bird science and conservation organisations and government agencies. The report is the most comprehensive review of long-term data for US birds ever conducted. The results, the authors say, are “unsettling,” with bird populations declining across several key habitats, and many birds in need of immediate conservation help. Nevertheless, it also shows that, where conservation has been carried out, bird populations are recovering.

The report is based on extensive reviews of data from long-term monitoring, and uses birds as indicators of ecosystem health by examining population trends of species dependent on different habitats – grasslands, forests, wetlands, oceans, aridlands, islands and coasts.

The authors identified aridlands (including desert, sagebrush and chaparral habitats) as the habitat with the steepest population declines. There has been a 46% loss of birds in aridlands in states such as New Mexico, Arizona and Utah since 1968. There are also significant threats in grasslands across the country, with a decline in breeding birds like the bobolink and the eastern meadowlark of nearly 40% since 1968.

Habitat loss and fragmentation are the most consistent and widespread threats facing America’s birds in all habitats, but invasive species are also high up on the list. Introduced species have a particularly strong impact on islands, where native birds are restricted to smaller areas in which they can live. For example, one-third of all federally endangered birds are Hawaiian species. Introduced predators such as mongoose and rats take a huge toll on Hawaiian birds, and grazing livestock degrade habitats.

Yet many species have benefited from targeted conservation efforts. The decline in grassland birds mentioned earlier has actually levelled off since 1990 thanks to conservation. Shorebirds along the coast are being squeezed into narrowing strips of land due to human development, but there has been a steady 28% rise in populations of all 49 coastal species examined in the report. This is a direct result of the establishment of 160 national coastal wildlife refuges and nearly 600,000 acres of national seashore in 10 states. The creation and preservation of large swaths of forests in the Appalachian Mountains and the Northwest has also helped declining forest-dependent species such as the oak titmouse and the golden-winged warbler which have declined by nearly 20% in the west and 32% in the east, since 1968. Wetland species have been helped by legislation – increases in waterfowl populations are a result of the North American Wetlands Conservation Act, which has helped protect and restore wetland habitats.

Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell spoke of the launch of the State of the Birds report. ?”Because the ‘state of the birds’ mirrors the state of their habitats, our national wildlife refuges, national parks, national seashores, and other public lands are critical safe havens for many of these species — especially in the face of climate change — one of the biggest challenges to habitat conservation for all species in the 21st century,” she said. “The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management and other Interior agencies practice science-based, landscape-scale conservation of these lands and their wildlife in partnership with scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey. I am proud that these agencies have collaborated with the Smithsonian and many others on today’s report. The Department of the Interior looks forward to continued cooperation to address these habitat conservation challenges.”

In addition to assessing population trends, the report also created a Watch List of 230 species that are either endangered or are at risk of becoming endangered without conservation intervention. Of these species, 42 are pelagic (open ocean) species such as some albatross species which are at risk from increasing levels of oil contamination, plastic pollution and less prey fish due to commercial fisheries.

Unsurprisingly, 33 Hawaiian forest species feature on this list. The authors have dubbed Hawaii “the bird extinction capital of the world” because nowhere else has seen more extinctions since human settlement. Neotropical migrants (30 species in total) also appear on the list, due to threats at their Central or South American wintering grounds.

There are 33 birds that do not meet the watch list criteria but are declining rapidly in many areas. Hundreds of millions of breeding birds have been lost during the past 40 years. These birds may not be classed as endangered just yet, but the passenger pigeon was once a common species too. We must pay attention to the message that Martha left us with, and act quickly to halt declines and prevent extinctions of all America’s bird species.

No comments yet.